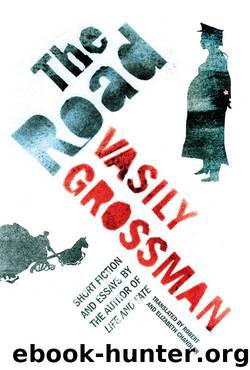

The Road: Short Fiction and Essays by Grossman Vasily

Author:Grossman, Vasily [Grossman, Vasily]

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Publisher: Quercus

Published: 2011-08-25T04:00:00+00:00

“Mama” – the next story in this section – is also set in the 1930s. It is based on the true story of an orphaned girl who was adopted by Nikolay Yezhov and his wife Yevgenia; Yezhov was the head of the N.K.V.D. between 1936 and 1938, at the height of the Great Terror. The orphaned girl, Natalya Khayutina, is still alive as we complete this introduction, and during the last twenty years she has given a number of interviews to journalists. Her story is of interest in its own right, independently of Grossman’s treatment of it, and is discussed in an appendix. Her own account of her first twenty years, however, diverges little from Grossman’s. As with his articles and stories about the war and the Shoah, Grossman seems to have done all he could to ascertain the historical truth, employing his imaginative powers not to create an alternative reality but to enter more deeply into the historical reality.

All the most prominent Soviet politicians of the time, including Stalin himself, used to visit the Yezhov household – as did many important artists, musicians, film-makers and writers, including Isaak Babel. We see these figures, however, only through the eyes of Nadya, as Grossman calls the orphaned girl, or of her good-natured peasant nanny. Grossman leads us into the darkest of worlds, but with compassion and from a perspective of peculiar innocence – the nanny is described as the only person in the apartment “with calm eyes”. Grossman’s evocation of Babel’s ambivalence, his uncertainty as to what world he belongs to, is especially moving. For the main part, Nadya has no difficulty in distinguishing between the politicians who visit her father and the artists who visit her mother. Babel, however, confuses her; on the face of it, he has come to see her mother, but he looks more like her father’s guests and Nadya perhaps senses that it is indeed her father who interests Babel more deeply.

Grossman wrote this story nearly twenty-five years after Babel had been shot. Grossman admired Babel, and he would probably have considered it wrong to make any public criticism of such a tragic figure. In conversation, however, Grossman was more forthright. Lipkin remembers telling Grossman how, in 1930, he had heard Babel say, “Believe me […] I’ve now learned to watch calmly as people are shot.” Lipkin quotes Grossman’s response at length: “How I pity him, not because he died so young, not because they killed him, but because he – an intelligent, talented man, a lofty soul, pronounced those insane words. What had happened to his soul? Why did he celebrate the New Year with the Yezhovs? Why do such unusual people – him, Mayakovsky, your friend Bagritsky – feel so drawn to the O.G.P.U.? What is it – the lure of strength, of power? […] This is something we really need to think about. It’s no laughing matter, it’s a terrible phenomenon.”* There are no such criticisms in “Mama”, but Grossman delicately hints at

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Tidewater Tales by John Barth(12639)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11793)

Tell Tale: Stories by Jeffrey Archer(9009)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6854)

The Mistress Wife by Lynne Graham(6465)

The Last Wish (The Witcher Book 1) by Andrzej Sapkowski(5440)

Dancing After Hours by Andre Dubus(5267)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4370)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4016)

The Secret Wife by Lynne Graham(3901)

Maps In A Mirror by Orson Scott Card(3877)

Tangled by Emma Chase(3738)

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges(3614)

The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros(3448)

A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms by George R R Martin(3298)

Girls Who Bite by Delilah Devlin(3242)

You Lost Him at Hello by Jess McCann(3055)

MatchUp by Lee Child(2867)

Once Upon a Wedding by Kait Nolan(2779)